In: EUROLINGUA & EUROLITTERARIA 2009. - Liberec: Technická univerzita v Liberci, 2009. - ISBN 978-80-7372-544-0. - (2009), s. 361-365.

In: EUROLINGUA & EUROLITTERARIA 2009. - Liberec: Technická univerzita v Liberci, 2009. - ISBN 978-80-7372-544-0. - (2009), s. 361-365.

Simona Hevešiová

Abstract:

In 2004, the Repertory Theatre in

The notoriously known hysterical reception of Salman Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses, manifested (apart from other things) by the burning of the book, the issuance of fatwa that forced Rushdie into hiding and the death of its Japanese translator, exposed the sensibilities of literary representation. These disquieting protests and perturbations only confirmed that imaginative literature is not free from political, religious or ethnic tensions and is far from being viewed as a space for creative expression of the artist. In words of James Procter: The emphatic rejection of The Satanic Verses, by the very communities it appeared to represent, highlighted the crisis of representation which has been a recurring feature of the reception of black and British Asian fiction since 1980s (Procter, p. 102). Hanif Kureishi, a British-born writer of Pakistani origin, has been, for example, frequently criticized by members of the Asian community for their negative portrayals in his fiction. His texts often defied the stereotypical representations, being full of drugs, sex, homosexuality and other atypical or inappropriate behavior; but Kureishi vehemently refused to be forced into the role of a spokesperson.

Similarly, Monica Ali’s novel Brick Lane inspired comparable reactions within the Bangladeshi minority living in

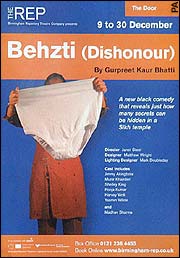

Tumults over a fictitious work were flared also in December 2004 when the second play by a British-born Sikh playwright Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti called Behzti (Dishonour) has been produced by the Birmingham Repertory Theatre. This time, however, riots and physical violence came into play and the situation escalated to such an extent that further performances of the play had to be canceled and the writer went into hiding (hence the obvious parallel with Rushdie’s case which lead to the label Behzti affair). The Sikhs marked the play as offensive to their religion and faith since it situated insulting actions and abominable behavior to a sacred place, i.e. to a Gurdwara (Sikh temple). Talks between the theatre and local Sikh representatives were initiated; yet apart from the fact that no results were achieved, even the very meaning of the attempted dialogue was misunderstood by the parties involved. While the Sikhs referred to the meetings as to negotiations that were supposed to lead to changes in the offensive content, the theatre preferred the words consultations or conversations (Grillo, 2007, p. 18). So what exactly made the play so debatable?

The play opens with a prologue that displays a rather complicated mother-daughter relationship. The eccentric Balbir Kaur, a physically disabled widow in her late fifties, is exposed in full vulnerability in front of her 33-year-old daughter Min who takes care of her. The exchange, spiced up by coarse language and rude remarks, makes it clear that they are getting ready to attend some religious ceremony in a Sikh temple. While Min is looking forward to participate in the religious celebrations that she had not attended since she was a little girl, she does not seem to know at first that her mother, who is in her own words not bothered with the holy things written in the book (Bhatti, 2004, p. 30), has other plans with her. Balbir wants Min to speak to Mr. Sandhu, the Chairman of the Gurdwara’s Renovation Committee and a person of authority, who is believed to possess a list of the most respectable Sikh men, i.e. potential husbands for Min. Min is tied to her mother who is not able to take care of herself and thus neglects her personal life. Balbir’s decision to find a husband for her is, as she herself proclaims in the play, intended to show her daughter life outside their house and secure her future.

The remaining parts of the play are then situated in Gurdwara, a sacred place for the Sikhs where celebrations of the birthday of Guru Nanak are taking place. Balbir and Min are accompanied by Elvis, Balbir’s non-Sikh home carer, so the text also contains some instructive passages introducing basic aspects of the religion as Min is relating them to him. Nevertheless, it is obvious right from the opening scene in Gurdwara that not all Sikhs come to the temple to pray and find comfort in god. We are introduced to Balbir’s old friends Polly and Teetee who steal shoes from the shoe rack in the temple and call other people hypocrites while both of them pretend not to know anything about the terrible deeds that happen in Mr. Sandhu’s office; later on Polly attempts to seduce Elvis who is in love with Min.

Balbir informs them that Min is going to talk to Mr. Sandhu in order to find a husband; Teetee’s question if she is sure that that is what she wants for her daughter foreshadows the dishonest practices of Mr. Sandhu, yet Balbir is totally ignorant of them (as is the reader/spectator at this point). When Min is thrown into his office, the existence of the famous list of potential husbands is denied since it functions only as a lure for young women to visit Mr. Sandhu’s office without him being suspected of doing anything amoral. Min discovers, as Mr. Sandhu (emotionally struck by her resemblance to her dead father) admits it to her, that her father Tej had a homosexual affair with him. The accidental discovery by little Min many years ago distressed her father to such an extent that he jumped out of a train and ended his life. For this reason, Mr. Sandhu blames Min for Tej’s death. The scene then ends with Mr. Sandhu raping Min whose screams merge with music from the worship area (another detail that the Sikh representatives objected to).

As it turns out Mr. Sandhu’s practices are a public secret; no one, however, dares to protest since he is a powerful and rich man, able to influence other people’s lives – both in a positive and negative way. As Mr. Sandhu himself remarked: Whatever things look like, there is always another story, always the truth underneath the show. After a while we get used to the disappointment (Bhatti, 2004, p. 108). It is Teetee who tells Balbir the truth in the end. Unable to grasp the grim consequences of her fatal decision, Balbir murders Mr. Sandhu in an act of desperation and thus completes the long list of detestable acts committed in the Gurdwara.

In fact, the play might have astonished even a non-Sikh readership since the scope of disgraceful, inappropriate or shocking subject matters (or whatever we call them) was rather wide (if not too wide) – ranging from stealing, drug addiction, homosexuality, hypocrisy, violence, verbal abuse to rape, suicide and murder. To some people the play may appear as overloaded with negative images and behavior which are de facto all attributed to the Sikh community and that was precisely the stumbling block. Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti explains this strategy in the foreword to the play:

I find myself drawn to that which is beneath the surface of triumph. All that is anonymous and quiet, raging, despairing, human, inhumane, absurd and comical… I believe it is necessary for any community to keep evaluating its progress, to connect with its pain and to its past (Bhatti, 2004, p. 17, emphasis added).

As Ralph D. Grillo remarks Sikh representatives were prepared to accept much of the play’s content, provided that changes were made to the setting and use of symbols (2007, p. 22). As for the setting, a suggestion was made to situate the events of the play to a community center instead of a temple; the severest objection was raised to the inappropriate juxtaposition of terrible deeds and sacred symbols (ibid., p. 7). In this context, Samuel Beckett’ s short story First Love may come to one’ s mind as a comparable example. Beckett’s story which succeeded to violate several aspects of the Western cultural code depicts fragments from a nameless man’s life who is coping with what is perceived as his first love. There is a scene in the story where the man, sitting on the toilet, struggles with constipation. At the same time, he is looking at an almanac with the picture of Jesus:

At such times I never read, any more than at other times, never gave way to revery or meditation, just gazed dully at the almanac hanging from a nail before my eyes, with its chromo of a bearded stipling in the midst of sheep, Jesus no doubt, parted the cheeks with both hands and strained, heave! ho! heave! ho! (Beckett, 1974, p. 15).

Clearly, by referring to these disparate images in one sentence and placing Jesus into a rather unusual context (to use a milder term) Beckett desecrated the sacred. James Joyce’s masterpiece Ulysses also contains similar juxtapositions, the sacred and the secular being confronted in a very direct way which was perceived by some recipients as offending. Bhatti’s explanation for the provocative content of her play is as follows:

I believe that drama should be provocative and relevant. I wrote Behzti because I passionately oppose injustice and hypocrisy. And because writing drama allows me to create characters, stories, a world in which I, as an artist, can play and entertain and generate debate (Bhatti, 2004, p. 18).

Yes, Behzti definitely did generate debate. The debate was, however, somewhat misdirected from the author’s intention and the message of the text which were veiled by the passionate talks about the external events rather than the play itself. The discussion was more or less reduced to questions of incommensurability and incompatibility of religious and secular values in a multiethnic, multicultural, multi-faith society and to the rights and limits of freedom of speech and the protection of religious sensibilities (Grillo, 2007, p. 6). Unavoidably, the interpretation of the text having been influenced by all these issues drifted away from a disinterested reading (if that is possible at all). A solely literary examination of the play’s events may, however, uncover a story with a very straightforward message.

Apart from or rather beyond the religious and cultural context, Behzti tells a simple story anyone can relate to. If Gurpreet Bhatti were not regarded as a spokesperson for the Sikh community (which she is not), another, more human dimension of the play would emerge. Behzti discusses questions of authority and abuse of power, hypocrisy, injustice and pretence – notions which are not attributed culturally or religiously. It portrays people living in pitiful and depressing conditions that are dependent on and rely on those having the possibilities to help them. But were the helping hand is expected, none is offered; instead, Mr. Sandhu keeps misusing his position and authority for years because he lives in a society where material goods, well-being and the fear of authority predominate over honesty, truthfulness and self-respect and where hypocrisy is tolerated. The religious dimension into which the play was placed can be easily transformed to any other context where power and authority play a role. Behzti presents a universal warning. And perhaps those who are affronted by the menace of dialogue and discussion, need to be offended (Bhatti, 2004, p. 18).

Bibliography:

Beckett, S. First Love and Other Stories. New York: Grove Press, 1974.

Bhatti, G.K. Behzti (Dishonour). London: Oberon Books, 2004.

Donkervoet, G. The Controversy that is Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti. Available at: http://www.sas.upenn.edu

Grillo, R.D. Licence to offend? The Behzti affair. Ethnicities, 2007, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 5-29

Kennedy, M. In a sense, if you come under fire from those conservative people, you must be doing something right, 2006. Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2006/jul/28/bookscomment.books

Procter, J. New Ethnicities, the Novel, and the Burdens of Representation. In A Concise Companion to Contemporary British Fiction. English, J.F. (ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006, pp. 101-120.