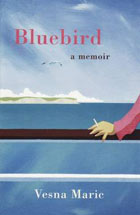

Vesna Maric: Bluebird. London: Granta, 2009.

Reviewed by Simona Hevešiová

In: Ars Aeterna - Art in Memory, Memory in Art, Vol. 1, No. 2 / 2009, ISSN 1337-9291, pp. 123-4.

In 1992, a war breaks out in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Motivated by ethnic and religious differences, the conflict affected the households of millions of people. Zlata Filipović, an eleven-year-old girl living in Sarajevo, records the changing pace of her life in her diary. What starts as the ordinary hobby of a carefree teenager soon turns into a terrifying and poignant account of the horrors of the war. The skiing trips, MTV charts, and chats with her friends are supplanted by shelling, and hiding in dark cellars. Zlata’ s Diary, published in 1993 (translated into Slovak in 1994), has become an international bestseller, with Zlata referred to as the Anne Frank of Sarajevo. The very form of the diary enabled Zlata to record her immediate emotions and worries as the world she had known disappeared in front of her eyes. The personal and the public intermingle, and the reader is provided with a first-hand account of the war conflict.

Fifteen years later, Vesna Maric, who is only four years older than Zlata, revisits her recollections of the conflict in her memoir Bluebird, published by Granta this year. The book opens with Vesna’s memory of TV footage depicting demonstrations in Sarajevo; suddenly, a young student is shot by a sniper and becomes the first official victim of the war. Those who expect to find other bloody accounts of the war will be, however, disappointed. Unlike Zlata Filipović, who remained in Bosnia until December 1993, Vesna fled her hometown Mostar soon after the war started. The memoir thus consists primarily of her experiences as a refugee struggling in a new environment. Maric provides hardly any background information or historical-political context for the war; therefore, some readers might feel a little bit lost at the beginning. At first sight, this lack of context may seem like a defect, weakening the message of the book by not depicting the core of the conflict. Yet Maric’s strength lies elsewhere.

Instead of presenting a mere chronological retelling of her personal experience, Bluebird consists of short episodic narratives which introduce Vesna’s fellow refugees and her new English acquaintances. At the age of sixteen, Vesna and her older sister boarded a charity bus heading for Penrith in the UK for safety. The four-day journey itself represented a remarkable spectacle exposing her tragicomic co-passengers: Dragan, “a factory manager and an amateur poet” (p. 30), who fell in love with a lady who never left her house; the 52-year-old Gordana, resembling Xena, the Warrior Princess, who announces that she is pregnant; the doctor’s wife who keeps smoking despite her heart problems; and the interpreter Esma who goes mad during the journey. Piteous moments are followed by grotesque ones, as the women fight for charity fur coats in a church or dress themselves in their finest clothes, thus contradicting the usual bedraggled image of refugees.

To be labelled as a refugee and to live as one is definitely not easy. Deprived of her home, her family, her language, the feeling of security, and even the diacritics in her surname, Vesna has to start anew. Slowly, she integrates into English society and finds new friends; her life finally becomes filled with casual activities – smoking, drinking, dating, studying… From time to time, letters from her father and friends or visits from other refugees remind her of the atrocities happening in her homeland.

After four years of waiting, Vesna is finally granted official refugee status. The news is received with relief; despite the fact that Hull (the city that she moved in) “will in future be voted the worst place to live” (p. 212), she likes her new home and her new life. The idea of living in Bosnia again is frightening. Yet as soon as she obtains her new papers, Vesna embarks on the journey home. Coming home is probably the most touching chapter of her memoir. Switching suddenly to second person narration, Vesna describes how it feels to come back home after the definition of home has been forcibly reedited. “It is difficult to grip on the time that has passed. Everything has been frozen in your memory since you left and now everything is different.” (p. 219) And the old slippers under her bed, symbolically, do not fit anymore.

Bluebird offers a remarkable reading, delightful and humorous despite its gloomy subject matters. At the same time, it succeeds in planting some pressing questions in one’s mind.